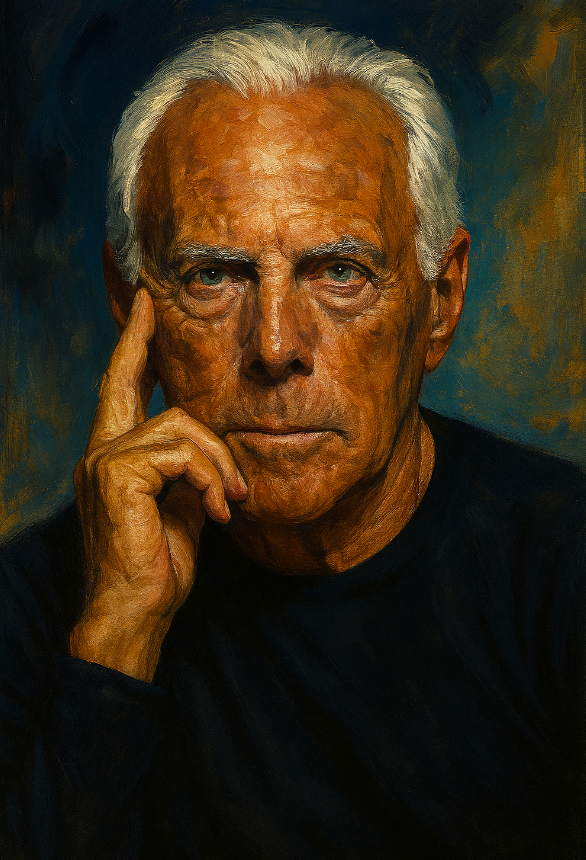

Armani arrived in fashion when the world still expected spectacle. He offered something else: a pared-back elegance that married impeccable tailoring with an almost meditative embrace of proportion and ease. The jacket he perfected — soft-shouldered, unfussy, and impeccably cut — did more than cover the body. It reframed what authority looked like on both men and women. Where bombast once defined status, Armani suggested that power could be conveyed in the fall of fabric, in the refusal of ornament, in the serene geometry of a well-made blazer.

His influence is easiest to read in the wardrobes of those he shaped: executives who sought dignity without display; actors who wanted presence without costume; everyday people searching for clothes that answered complexity with clarity. Armani’s work mattered because it gave people a practical vocabulary for inhabiting the modern world. He made the notion of the “uniform” aspirational without making it oppressive. He taught that meticulousness need not be ostentatious, and that the best clothes feel inevitable — as if they had always belonged to the person who wears them. There is a moral argument embedded in Armani’s aesthetic, one that privileges discretion, longevity and craftsmanship. In an industry often driven by novelty, Armani insisted on patience. He preferred fabrics that aged well, palettes that matured, and seams that survived repeated wear. That was not a merely aesthetic stance; it was a philosophical one. In an age of accelerating consumption, Armani’s restraint reads as an act of cultural stewardship. He reminded us that taste, like virtue, accrues through discipline.

Armani’s sensibility also altered gendered dress. His suits for women — crisp, languid, and calibrated to move with the body — were emancipatory precisely because they offered elegance without diminishment. They did not masculinize; they translated dignity into forms that worked for women’s lives. In doing so he participated in a broader cultural reconfiguration of who could look powerful and how power might be projected. The Armani woman was never about mimicry; she was about authority rendered in fabric and cut, a quiet manifesto against theatricality. Yet to reduce Armani to a single silhouette or a handful of jackets is to miss the breadth of his practice. Over decades he built an empire that spanned couture, ready-to-wear, accessories, home goods and hospitality. His genius lay in maintaining a coherent point of view across these varied domains: the same sense of proportion, the same devotion to tactile sensibility, and the same insistence on design that improves daily life. Whether a shirt, a suit, a hotel suite, or a fragrance, an Armani object aimed to be both useful and uplifted.

His relationship to cinema was another vector of influence. Collaborations with filmmakers and costume designers placed Armani’s clothes on some of the most famous bodies of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. On screen, his garments were not merely wardrobes; they were instruments of character — tools directors used to communicate nuance and interior life. The synergy between Armani and film helped to disseminate his aesthetic globally, making his vision familiar across languages and cultures.

Armani’s approach to branding is instructive for anyone thinking about taste at scale. He built not by shouting his name across every product category but by cultivating a mood so recognizable that the brand became synonymous with a certain way of being. It was an exercise in consistency and patience: an accumulation of small, uncompromising design choices rather than episodic gimmicks. That discipline allowed a single sensibility to feel luxurious without ever degenerating into caricature.

There are critiqued corners of Armani’s legacy, as there are with any figure who occupies such cultural prominence over many decades. Some argued that a wardrobe anchored in beige and muted tones could feel detached from the exuberant diversity of lived experience. Others questioned whether sartorial restraint risked excluding those who seek self-expression through flamboyance and color. These critiques are valuable because they remind us that elegance need not be the only path; plurality is a healthier cultural condition. Yet even critics often acknowledged the clarity of Armani’s vision and the craftsmanship behind it.

What Giorgio Armani leaves behind is less a list of hits than a set of idioms — architectural choices in clothing that entered common parlance. The soft shoulder, the unstructured blazer, the muted palette, the devotion to drape and line: these are the touchstones that countless designers have borrowed, recombined and reinterpreted. His legacy is thus both taught and absorbed, a pedagogy of taste that operates quietly through example rather than decree.

On a human level, Armani’s story also charts the particularities of an Italian life that became global without losing its roots. He drew from a Mediterranean reverence for touch and craft, from a culture that prizes the material and the artisanal. Yet his work never felt parochial. It was cosmopolitan precisely because it was grounded: if Italian tailoring supplied the hand, Armani’s vision provided the mind. He knew how to translate the warmth of tradition into garments that spoke to contemporary life.

The role of mentorship and sustained collaboration in his career cannot be overstated. Armani’s houses were laboratories where cutters, weavers, and pattern-makers honed their art. He cultivated teams who could interpret his intuition with technical rigor. In an era when the cult of the lone genius often obscures collective labor, Armani’s longevity owed much to those quiet partnerships. His success was a demonstration of what sustained craftsmanship, aligned with a disciplined aesthetic, can accomplish.

There is also a civic dimension to his influence. Fashion, when treated with seriousness, holds sway over public life. It shapes the way institutions — courts, boardrooms, stages — imagine dignity. Armani’s taste suggested that the public sphere could be dignified without being pompous; that civility might be expressed through restraint rather than spectacle. If democratic societies need styles that allow people to present themselves with seriousness and care, Armani’s work provided a model.

To write about Armani as he exits the stage is to reckon with the way fashion mediates memory. Clothes are repositories of moments — weddings, films, decisive boardroom meetings — and Armani’s clothes have been present at many of those moments for generations. They become heirlooms not simply because of their price tag, but because of the way they sit in the life of a person: a well-cut blazer that reads as confidence, a shirt that becomes a favorite, a suit worn to an interview that alters a life’s trajectory. The emotional economy of Armani’s work is as real as its commercial one.

If there is a lesson for designers, patrons, and readers of fashion journalism, it is this: longevity in taste is not the same as stasis. Armani’s aesthetic remained consistent because it was elastic, able to absorb new contexts without betraying its core. That ability to adapt without losing identity is the rare alchemy of great design. It is what allowed Armani to remain relevant from the postwar years into the tumultuous cultural shifts of the twenty-first century.

As we catalog his achievements — the runways, the boutiques, the smell of an Armani fragrance, the texture of a jacket — we should also recognize what he taught about the ethical life of objects. He argued, through example, that beauty and restraint can coexist with pleasure; that the objects we keep close to our bodies can be made with care that honors both maker and wearer. In an era of environmental urgency and cultural acceleration, that ethic feels less quaint and more necessary.

Giorgio Armani’s departure invites not only mourning but also a recalibration of values. The industry he helped shape must now reckon with its future: how to honor craft while embracing diversity, how to insist on quality in a world that privileges speed, how to use the cultural reach of fashion to uplift rather than commodify. Armani’s life offers a blueprint for some of these answers, not by prescribing a single course but by demonstrating the power of taste exercised with humility.

In the end, Armani’s most enduring gift may be the quiet permission he offered: permission to pursue elegance as a form of seriousness, permission to treat clothes as instruments of dignity, permission to believe that restraint can be as electric as extravagance. That is a lesson suited to designers and citizens alike. The jacket he perfected will continue to circulate in closets and on screens and in photographs — modest artifacts that carry a large idea: that the way we dress is a way of declaring what kind of world we prefer to live in.

We say goodbye not only to a designer but to a sensibility that argued, for decades, that refinement need not be brittle. Giorgio Armani taught us that simplicity can be rigorous, that craft can be compassionate, and that in the quiet geometry of a suit there can be a profound expression of character. For those reasons, and many more, his work will endure — not as museum relic, but as living practice, woven into the daily act of getting dressed, of meeting the world with readiness and grace.